Journal

Restoring Atlantic Temperate Rainforests - A Lesson From The Salmon Forests of Canada

It has been fascinating to stumble into the world of rainforest restoration in the UK, at what feels like a very pivotal time for cultural identity; as the lichen and fern-clad, rain-sodden woodlands of coastal UK are increasingly being reimagined as Atlantic Temperate Rainforests. Having moved over from Vancouver Island, Canada, I’ll admit that the last thing I expected to encounter in the UK was rainforest. Rather, I had pictured wind-battered coastal cliffs, rolling meadows with the occasional craggy old oak, and Heathcliffe emerging from the mist of a heather-clad moorland.

I had been in the vicinity of rainforest restoration for some time in Canada, where I learnt of incredible work being done by Coastal First Nations and organisations such as Reddfish Restoration. This work was being carried out throughout Nuu-Chah-Nulth territories on the West Coast of Vancouver Island. One key thing that stood out for me on the Island was the focus on restoring ecosystems at scale. In these ‘salmon forests’, it seems that one of the most crucial elements for rainforest integrity is river and intertidal restoration, and vice-versa. In the forests of the Pacific Northwest, the connection between ocean and rainforest, maintained through the thread of the river, forms the backbone of these vital habitats. So, restoration of any one habitat really must focus on them all. To illustrate this, studies have found that marine-derived nitrogen is transported hundreds of kilometres upstream in the bodies of the salmon, where bald eagles, bears, and wolves transport this vital nutrition further into the forest and even high up into the tree canopy.

Back on this side of the Atlantic, when I hear these conversations about stewarding, enhancing, and expanding the fragmented and vital Atlantic temperate rainforests, I can’t help but be struck with the feeling that the thread of how vital our rivers and coasts are to rainforests is missing, or at least underrepresented, from the conversation over here. The state of Atlantic Salmon, a distant relative of the Pacific Salmon, is dire. Now listed as endangered in the UK, populations are in crisis and have declined 70% in the last 25 years, with returns of just 50 fish counted on the River Dart in 2023, for example, according to the Fishtek Totnes Weir.

But what to do about our Salmon? Well, perhaps a good place to start is to think about the linkages between the rainforests that line the river valleys of salmon runs to the river themselves, and in turn their ocean-going fish. The question in my mind is how we can better manage our rivers, crucial riparian arteries between land and sea, alongside their linked rainforest habitat,s with our critically endangered Atlantic salmon in mind?

This past week, I was lucky to snag a spot at a Rainforest Management Day offered by the Woodland Trust in partnership with Plantlife and Natural England at Yarner Wood in East Dartmoor.

We saw an incredible example of this sort of riparian-based rainforest management playing out at Yarner Wood. The felling works that have been done have created biogenic (any natural feature that helps to slow the flow of water, such as woody debris) interventions to help slow and spread the flow of the river coursing through the site.

Salmon require cool, clean, oxygen-rich fast-flowing water with extensive gravel beds to spawn in. They are very vulnerable to changes in river water quality, temperature, and flow. By adding woody debris into the watercourse at Yarner Wood, sediment is caught and filtered, thereby improving water clarity and quality. Gravel is also trapped and filtered which optimises the rivers for salmon, as they require larger, smooth cobbles for spawning.

The next step, we’re told by The Woodland Trust team, will be to plant willow along the river bank, helping to provide appropriate shading to keep river temperatures optimal for salmon. Water temperatures beyond 16°C may result in salmon run declines; as warming temperatures cause salmon to become stressed and unable to spawn, and eggs also cannot persist in higher temperatures. Alongside providing shading, the saturated, humid sponginess of intact, functional temperate rainforests helps to moderate humidity and in turn, helps to optimise salmon stream temperatures. In addition to temperature regulation, riparian willow planting will also help to stabilise river banks thereby supporting runoff mitigation, and will also gradually add more biogenic woody material from the willow into the mix.

Overall, this filtering, slowing of flow, and re-connecting of rivers with their floodplains also provides the invaluable benefit of flood control for downstream communities and increases the resilience not only of the rainforests but the people around them.

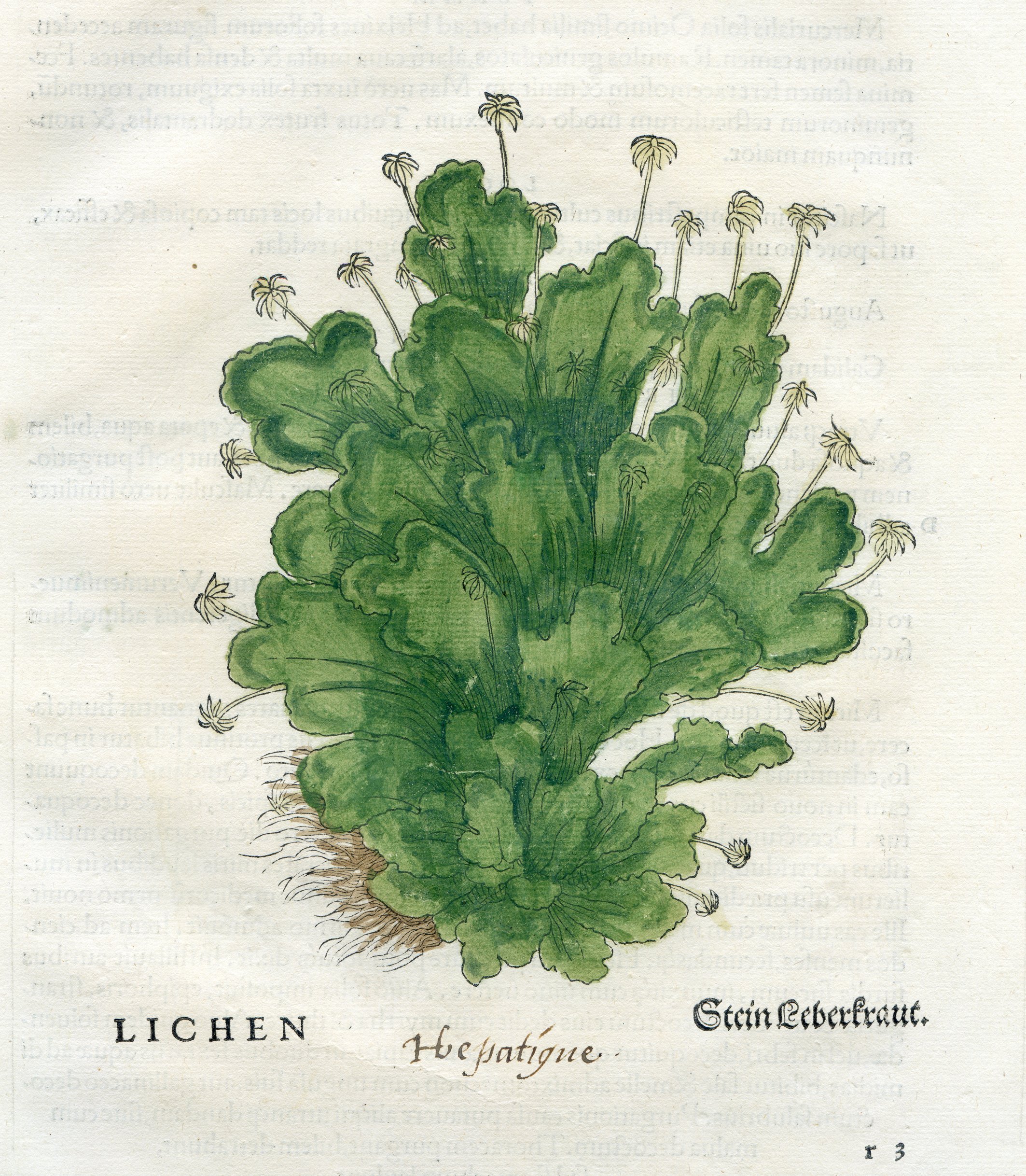

At the event, we learned from Sam Manning at the Woodland Trust that the three key components for functional temperate rainforests are good air quality (which bryophytes - lichen, mosses and liverworts rely on), light reaching through a somewhat open canopy (which bryophytes also require to photosynthesise), and ample water and rainfall to create appropriate humidity level within rainforests. The water bit is key. Centuries of drainage have removed and rearranged the way water flows through the land and have resulted in drier habitats, including our rainforests. Therefore, the key to restoring rainforest function is rewetting them; removing drainage, the addition of biogenic material, and allowing water to flow freely across floodplains, all to help raise the water table. This moistening of the whole forest has benefits not only for humidity regulation but also for the control of over-dominant plants such as bracken, which thrive in drier soils and don’t like soggy feet.

So as we manage rainforests, it becomes clear that a huge focus area should also be on managing water. Slowing, spreading, sinking it into the land, rewetting our woodlands, and thinking about managing riparian integrity will have cascading positive effects down to the coast. Where our beautiful Atlantic Salmon will join the rainforest story and help replenish upland habitats through their life cycle. Perhaps restoring a small patch of Atlantic temperate rainforest, in turn, can help strengthen the connections and integrity of an entire coastal ecosystem.

I would like to extend a huge thank you to the Woodland Trust, Plantlife, and Natural England teams for hosting everyone at Yarner Wood. As well, a huge shoutout to the tree works team that carried out the interventions on the ground at the event, based on the Rapid Rainforest Assessment results.

These works, such as thinning, coppicing, and bark-ringing will help open up the canopy, create standing deadwood, and diversify the dominance of single-age oak coppice currently present at Yarner. It was inspiring to see this work, alongside river restoration, playing out to ultimately encourage a more dynamic and resilient rainforest at Yarner Wood.

Woodland Trust Rainforest Recovery Website

In Season, In Place - Rediscovering What The Land Once Gave Us

For centuries, the people of Devon and Cornwall thrived on a diet shaped by their land and sea. From the Cornish Earlies, dug fresh from the rich soils of Cornwall, to the Mazzard cherries that once flourished in North Devon Orchards, the region's food reflected its heritage. Cider culture, too, was deeply ingrained in local life, with orchards covering the countryside, producing the sharp and sweet varieties that sustained generations. And then there were the humbler staples—swedes, pilchards, barley bread—once the backbone of working-class diets.

Yet today, much of this history is slipping away. Supermarkets offer instant satisfaction, with year-round produce sourced from thousands of miles away. Fast food and convenience meals have replaced the slow, seasonal rhythms that once dictated what we ate and when. The result? A disconnect from our heritage and the seasonal way of living.

South West Origins

The Cornish Early potato has been cultivated in the mild climate of Cornwall since at least the mid-1700s. Originally grown as a staple alongside pilchards, it wasn’t until the early 19th century that Cornish Earlies became a prized commodity. By 1808, they were being shipped across the UK, Europe, and even as far as Barbados and Newfoundland. Their unique taste, shaped by the coastal air and sandy soil, made them unlike any other potato—yet today, they are at risk of being forgotten in favour of mass-produced, uniform varieties.

A successful crop of Cornish Earlies grown using Hadfield Special Potato Manure, St Germans, Cornwall, circa 1910’s

The Decline of Cider Culture

Cider-making has been at the heart of Devon and Cornwall’s identity for centuries. Orchards filled with traditional apple varieties like Kingston Black, Dabinett, and Slack-ma-Girdle once produced rich, complex ciders that aged like fine wine. These weren’t just drinks—they were part of local ritual, culture, and community. But the rise of industrial cider-making has led to the dominance of mass-produced, sugar-laden alternatives. Small-scale cider makers are fighting to keep the tradition alive, but without consumer support, the unique, heritage ciders of the Southwest risk becoming nothing more than a nostalgic memory.

The Cider Works, originally built in 1935 for The Creedy Valley Cider Company, Crediton, Devon

Swedes, Barley, and the Lost Staples

Swedes, often associated with harsh winters and frugal cooking, were a mainstay in Cornish and Devonian kitchens. Alongside barley bread, they formed the foundation of many traditional dishes, from Cornish pasties to hearty stews. Oats, too, were a staple grain grown across Dartmoor and used in everything from oatcakes to slow-cooked porridge. And in wetter soils, rye and even Devon White Wheat—an old variety known for its nutty depth—thrived until industrial agriculture pushed them aside.

Today, these simple, nutritious foods are often overlooked, replaced by imported alternatives that bear little connection to the land and the people who once depended on them.

Coastal Foraging and the Ocean’s Pantry

Beyond farmland, the coastline offered another layer of seasonal food wisdom. Sea beet and samphire once filled pots and pans with salty brightness. Laver, a mineral-rich seaweed, was foraged from tidal rocks and stewed into laverbread. Shellfish like limpets and periwinkles were gathered from rock pools and served with vinegar or stewed in fish broths—humble, nourishing, and deeply rooted in place.

These wild foods weren’t delicacies. They were dinner. And their availability followed nature’s tide.

Mazzard Cherries: North Devon’s Lost Treasure

The mazzard or gean is a domesticated form of wild cherry (Prunus avium). In years gone by, they were widely grown in North Devon, particularly in the villages of Landkey, Swimbridge, and Goodleigh, where the trees thrived on the slopes of the Taw Valley in the damp, mild climate.

Mazzards were taken to the Pannier Market in Barnstaple and sold by the pound. It is said that in 1645, the future King Charles II sampled mazzard pie when he stayed with the Countess of Bath at Tawstock. Mazzards are gently cooked and served with Devonshire clotted cream or made into tarts or pies. As the 20th century progressed, mazzards fell out of fashion due to the substantial amount of labour required to protect and harvest the crop. After 1918, rural depopulation led to a decline in available pickers, making mazzard growing unviable.

Mazzard trees grow very tall, and farmers built long ladders to reach the top. There are five known strains of mazzard: Dun, Greenstem Black, Black Bottler, Small Black, and Hannaford. Landkey was also home to three varieties of indigenous apples: Stockbearer, Limberland, and Listener. Another special fruit tree from the area was the Landkey Yellow, a type of plum commonly used in hedgerows.

Prunus Avium, Mazzard Cherry Tree

Bringing Back Seasonal Eating: Listening to Nature’s Calendar

As well as becoming disconnected from our past and heritage, we have managed to miss the important vitamins and nutritious values that the land presents to us throughout the year. Think about it: in spring, just like us, everything starts to wake up and come out of hibernation. Then with the help of Mother Nature, we’re gifted exactly what our bodies need.

Take wild garlic, for example—abundant from late March through to May. Wild garlic has been traditionally used for its medicinal properties for centuries. It is known to have antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties, and may help lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels. It also supports digestion, boosts the immune system, and has anti-inflammatory effects. Rich in vitamins A and C, iron, magnesium, and manganese, it’s a perfect spring tonic.

Later in the year, elderberries ripen between August and October, ready to be turned into cough syrup or cold-preventing tinctures for winter. We often search far and wide for medicinal properties, sometimes from the other side of the world, when what we need is already on our doorstep. Nature is shouting at us to come back to our roots. She’s reassuring us that most of what we seek nutritionally is already here, in the soil and hedgerows of our native land.

Of course, for city folk, it's a different story. But that doesn’t mean you can’t be conscious. Even in supermarkets, pause for a moment. Ask yourself: what’s in season right now? How can I reduce the air miles of the food I eat? What impact is the harvest of this particular fruit or vegetable having on the environment?

When we eat seasonally, we're not just eating with the land—we're syncing with the ancient intelligence of our bodies. This isn’t romantic nostalgia. It’s biological design.

How We Find Our Way Back

Reviving these traditions doesn't mean turning back the clock—it means making conscious choices. Choosing a swede grown in Devon over a sweet potato flown in from Peru. Buying cider from a local orchard rather than a supermarket chain. Supporting farmers markets and small-scale growers instead of defaulting to big-box convenience.

Look out for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) boxes in your area or local farm shops offering weekly veg boxes.

Visit local Pannier Markets like those in Tiverton or Crediton, if you’re based in Mid Devon.

Support heritage fruit projects like the North Devon Mazzard Heritage Orchard.

Discover wild foods—many local foragers now run courses on seasonal plants and there are plenty in the South West.

“The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.” - Masanobu Fukuoka

Uncharismatic Species - The Unsung Heroes of Our Ecosystems

When we consider wildlife conservation in the UK, we often focus on charismatic creatures like beavers, roe deer or eagles. But what about the smaller, overlooked species that quietly sustain our ecosystems? These uncharismatic species may not be in the limelight, but their environmental contributions are essential.

Below, we’ll explore some underappreciated species native to the UK and uncover the vital roles they play in maintaining ecological balance.

Black Garden Ant (Lasius niger) - Nature’s Tiny Soil Engineers

A bustling colony of black garden ants is more than just a summer spectacle towards the fruit bowl; it’s a natural force that quietly enriches the earth beneath our feet. As these industrious insects tunnel through the soil, they aerate it, improving water infiltration and nutrient circulation, which enhances plant health. Beyond their underground work, they help break down organic matter, turning dead insects and plant material into rich nutrients that nourish the land. By preying on small pests like aphids, they act as tiny guardians of gardens and crops, reducing the need for chemical pesticides.

How to Support The Black Garden Ant :

Ditch the pesticides – Chemical treatments can wipe out ant colonies and disrupt the delicate soil ecosystem.

Encourage wild spaces – Letting areas of your garden remain untamed provides safe havens for ants to thrive.

Appreciate their role – Instead of seeing ants as invaders, recognise their contributions to a healthy environment.

House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) - The Declining Urban Companion

Once a cheerful presence in bustling cities and quiet villages alike, house sparrows are now disappearing at an alarming rate. Since 1970, the UK population has plummeted by over 30 million due to habitat destruction, pollution, and the loss of natural food sources. These charming little birds play a vital role in urban and rural ecosystems, feeding on aphids, caterpillars, and other insects that damage crops and gardens. Their seed consumption also helps with plant regeneration, making them silent stewards of biodiversity. As indicators of environmental health, a drop in sparrow numbers is often a warning sign of declining air quality and urban greening.

How We Can Protect The House Sparrow :

Plant native trees and shrubs to provide shelter and nesting sites.

Avoid excessive use of insecticides that eliminate their natural food sources.

Set up bird feeders with seeds, especially in urban areas where natural food is scarce.

Marsh Spider (Dolomedes fimbriatus) - The Silent Water Hunter

Gliding across the still waters of marshes and fens, the marsh spider is an agile predator, keeping insect populations in balance. Found in wetland habitats, this semi-aquatic spider preys on dragonfly larvae, pond skaters, and even small vertebrates like fish and tadpoles. It serves a crucial role in the food chain, providing sustenance for birds, amphibians, and larger insects. The presence of marsh spiders is a strong indicator of a healthy wetland environment, as they thrive only in unpolluted waters with abundant prey.

How We Can Protect The Marsh Spider :

Preserve wetland habitats, as they are crucial for marsh spiders and many other species.

Avoid excessive pesticide use, which can disrupt insect populations and impact the spider’s food sources.

Change perceptions – Rather than fearing spiders recognise their vital role in nature.

Grey-Carpet Moth (Lithostege griseata) - The Nighttime Pollinator

While butterflies bask in the spotlight, moths work quietly through the night, pollinating flowers that bloom after dusk. The grey-carpet moth, a small but important species, plays a key role in supporting plant life, particularly in East Anglia and parts of West Wales. As it flits from bloom to bloom, it ensures that nocturnal plants, such as evening primrose, can reproduce. Moths also serve as an essential food source for bats, birds, and other nighttime predators. Alarmingly, their decline signals issues like habitat destruction and pollution, threatening the delicate balance of ecosystems.

How We Can Protect The Grey-Carpet Moth :

Reduce artificial lighting at night, as it can disorient moths and interfere with their natural behaviours along with other nocturnal species.

Plant native flowers that bloom at night provide food sources, like Evening Primrose - the yellow silken blooms of the flower open to release their scent as the sun goes down attracting the moths to an eventide aroma.

Limit pesticide use – Chemicals kill caterpillars and adult moths, disrupting their lifecycle.

Common Toad (Bufo bufo) - The Keystone Slug Patrol

With their warty skin and slow, deliberate movements, common toads may not seem like heroes, but they play a crucial role in maintaining balanced ecosystems. These nocturnal hunters feast on slugs, snails, and insects, making them a gardener’s best friend. Without toads, these pests can quickly overrun gardens and farmlands, damaging crops and flowers. As a keystone species, their presence or absence reflects the overall health of an ecosystem. Toads also serve as prey for birds and snakes, connecting them to the broader food web. However, habitat destruction, pollution, and road traffic during migration threaten their numbers.

How We Can Protect The Common Toad :

Avoid using slug pellets and pesticides.

You can also support the common toad by leaving part of your garden to grow wild, giving toads somewhere safe to hibernate and overwinter.

Be well aware of them migrating across roads to mate during the spring.

Create small ponds or damp hiding spots in gardens to shelter them.

Preserve natural habitats, especially woodlands and wetlands, where toads thrive.

Carrion Beetle (Nicrophorus silphidae) – Nature’s Cleanup Crew

Despite their eerie-sounding name, carrion beetles are vital recyclers, breaking down dead animals and returning nutrients to the soil. Without them (40% of the UK’s insects are beetles), carcasses would take far longer to decompose, increasing the risk of disease spread. Some species even bury small carcasses, fertilising the ground and creating a nurturing space for their larvae. Alarmingly, habitat destruction threatens these unsung environmental custodians.

How We Can Protect The Carrion Beetle :

Protect forests and natural landscapes where carrion beetles perform their ecological roles.

Educate others about their importance instead of viewing them as scavengers.

Reduce habitat destruction and fragmentation, as they rely on undisturbed areas for survival.

Earthworms (Lumbricus terrestris) – The Underground Engineers

Beneath our feet, earthworms perform an invaluable service, aerating the soil and transforming organic material into nutrient-rich compost. Their castings, or waste, serve as natural fertilisers that enhance plant growth. Without earthworms, the soil would become compacted and less hospitable to plant roots, affecting everything from backyard gardens to large-scale agriculture. However, intensive farming, chemical fertilisers, and over-tilling are threatening their populations.

How We Can Protect The Earthworm :

Avoid over-tilling soil, as it can destroy their burrows and habitat.

Reduce the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, which can harm worm populations.

Support organic farming and gardening practices that encourage healthy soil ecosystems.

Seagulls – The Adaptable Guardians of the Coast

Often seen soaring over the sea or scavenging along shorelines, seagulls are among the most misunderstood birds. These highly intelligent and adaptable creatures play a crucial role in coastal and urban ecosystems. Seagulls move nutrients between land and sea. Their droppings (guano) are rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, which fertilise coastal plants, benefiting dune vegetation, marshlands, and seabird nesting sites. Seagulls are also skilled hunters, feeding on fish, crustaceans, and insects, keeping local populations in balance.

Seagulls are excellent problem-solvers, capable of using tools, recognising human behaviours, and even working together to access food. Their ability to thrive in both wild and urban environments has led to their reputation as opportunistic birds, but their presence is essential for maintaining ecological stability. Unfortunately, seagulls face increasing threats from habitat destruction, pollution, and food shortages due to overfishing.

How We Can Protect The Seagull :

Avoid littering – Plastic waste and discarded fishing gear pose serious threats to seagulls and marine life.

Respect their natural diet – Feeding seagulls processed food can harm their health and encourage dependency on human sources.

Protect nesting sites – Coastal development and human disturbance can disrupt breeding colonies.

Advocate for sustainable fishing – Overfishing depletes the gulls’ natural food sources, forcing them to scavenge in urban areas.

From the industrious black garden ant to the adaptable seagull, each of these species plays a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of Britain’s natural ecosystems. Whether found in our gardens, woodlands, wetlands, or coastal areas, these creatures contribute to the health of our environment—pollinating plants, controlling pests, enriching the soil, dispersing seeds, and keeping ecosystems in check. They are the silent workforce that supports the lush landscapes, thriving wildlife, and agricultural stability that Britain relies upon.

However, British biodiversity is under threat. Habitat loss, pollution, climate change, and urban expansion have led to declines in once-common species like house sparrows and common toads. The overuse of pesticides and disruption of natural food chains further endanger the balance that has sustained these species for centuries. Without them, the resilience of our woodlands, farmlands, and coastal environments could begin to unravel.

Protecting British wildlife starts with small changes—allowing wild spaces to flourish in our gardens, reducing chemical use, preserving natural habitats, and educating others on the importance of these creatures. By valuing the role of ants in soil health, sparrows in pest control, or even seagulls in waste management, we can shift our perception and ensure these species continue to thrive.

Britain’s biodiversity is not just a backdrop to our lives—it is the foundation of a healthy and balanced environment, something we should all be fighting for.

Laying the Land - The Vital Role of Hedgerows

A still, clement February morning, the whisper of branches being laid, the scent of woodsmoke from the Digg & Co. Studio curling through the crisp countryside air —hedge-laying is as much an art as it is a necessity. In the heart of the English countryside, hedgelayers have been quietly shaping the land for centuries, their craft ensuring that these living boundaries continue to thrive.

At Digg & Co., our team recently took part in this age-old practice, reconnecting with the land in a deeply meaningful way. Hedgelaying is more than just a rural tradition; it’s a vital force in farming, conservation, and climate resilience. In this blog, we’ll explore why it matters and why these living threads should never be left to unravel.

Hedgelaying is an ancient craft, one that has helped shape Britain’s patchwork landscape for over a thousand years. The oldest surviving hedgerow in England to date is thought to be Judith's Hedge in Cambridgeshire, which is reputed to be over 900 years old. Originally developed as a practical method for containing livestock and marking boundaries, hedge-laying ensured that hedgerows remained dense and healthy.

Each region in the UK has developed its style, reflecting the land it serves. The Midland style, with its clean-cut stems, keeps cattle at bay, while the Devon style, tightly woven and stock-proof, provides extra sturdiness against the elements. These techniques passed down through generations, remind us that hedgerows are not static features of the countryside but dynamic, evolving elements shaped by human hands.

A Haven for Wildlife

Hedgerows are among the richest habitats in the British landscape, supporting over 2,000 species, from nesting birds and small mammals to bees and butterflies. In an era of biodiversity decline, a well-laid hedge is more important than ever.

By cutting and partially bending stems, hedge-laying stimulates fresh growth, creating dense, intertwined branches that offer better shelter and food sources. Birds like Robins (Erithacus rubecula) and Bullfinches (Pyrrhula pyrrhul) find nesting sites in the thick cover, Gatekeeper Butterflies rely on grasses at the hedge base for their caterpillars and nectar from hedge flowers for adults, while dormice and hedgehogs use them as corridors, safely navigating the countryside. Without proper management, hedges grow thin and gappy, reducing their ability to support this extraordinary diversity of life.

Autumn Hedgerow, Cornwall by Amanda Hoskin

Hedgelaying and Sustainable Farming

Beyond wildlife conservation, hedge-laying plays a crucial role in sustainable farming. Hedges act as natural windbreaks, reducing soil erosion and protecting crops. They provide shade and shelter for livestock, helping them conserve energy during harsh weather.

Hedgerows also support natural pest control by attracting beneficial insects and birds that feed on crop-damaging pests. Their deep roots help prevent flooding by slowing water runoff, while their dense structure absorbs carbon, making them a valuable ally in the fight against climate change. A well-managed hedge isn’t just a scenic feature—it’s a working part of the farm, contributing to both productivity and environmental resilience.

Hedgerows for Everyone

Even for those who aren’t farmers or conservationists, hedgerows are an essential part of our shared landscape. They define the English countryside, offering a sense of continuity and belonging. Walking beside an old hedgerow, one can see its history woven into its structure—ancient oaks standing like sentinels, blackthorn and hawthorn twisting together, wildflowers bursting into life along its base.

These living barriers also play a key role in climate adaptation. They provide crucial shade in increasingly hot summers and form natural flood defences. With Devon (along with the rest of the UK) continuing to experience wetter winters, natural flood management has become a crucial part of our way of living. Hedgerows help slow the movement of water across the land, reducing the risk of flash floods and soil erosion. For communities, they are a space of quiet refuge, connecting people with the natural world in a way that tarmac and fences never could.

Our Experience - Digg & Co. in the Thicket

In February, Digg & Co. team members took part in a hedge-laying session, working together to revive a tired stretch of hedge. As the stems were cut and laid, the hedge was given new life—thicker, stronger, and ready to flourish in the coming spring.

There’s something deeply satisfying about working with the land in such a hands-on way, using traditional tools and time-worn techniques to restore something that will outlive us all. As we warmed our hands on mugs of hot oxtail soup, pricked by blackthorn and warming up by the fire, the experience reminded us how vital this practice is—not just for the landscape, but for us as a team. It reinforced our commitment to thoughtful, sustainable landscape design—one that honours these living structures rather than replacing them.

Each time we take part, our understanding of the land deepens. With every cut and lay, we’re not only strengthening our skill set but also strengthening our connection to the countryside itself.

Keeping the Craft Alive

Despite its many benefits, hedge-laying is at risk of fading into obscurity. The decline of traditional countryside skills and the push for mechanised farming have left many hedgerows neglected or lost altogether. But hope remains. Training schemes, volunteer groups, and organisations like the National Hedgelaying Society are working hard to keep this craft alive.

For those interested, there are plenty of ways to get involved. Landowners can invest in hedge-laying for their farms, while volunteers can join conservation groups dedicated to hedge restoration. Even supporting farmers and land managers who maintain hedgerows can make a difference.

Hedgerows are more than just boundaries; they are lifelines, histories woven into the land, and guardians of nature’s balance. To lay a hedge is to stitch together past and future, ensuring that these vital corridors remain for generations to come.

At Digg & Co., we believe that landscape design should work with nature, not against it. Hedgelaying is a perfect example of how human hands can enhance the natural world rather than diminish it. By keeping this tradition alive, we not only strengthen our countryside but also deepen our connection to the land we and other species call home.

So next time you pass an ancient hedge, take a moment to look closer. There’s more life woven into those twisted branches than meets the eye.

Unveiling Spring’s Subtle Heralds in Mid Devon

As winter's grasp loosens, the countryside around us awakens with understated signs of spring. Beyond the familiar daffodils and blackbirds, a closer look reveals nature’s more subtle cues of the season’s return. These overlooked signs—small, unassuming, yet deeply rooted in history and folklore—whisper their presence to those who take the time to notice.

One of the earliest botanical indicators of spring in the region is dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis), a humble green plant that flourishes in the dappled shade of ancient woodlands. Its name alone hints at its folklore—historically, it was believed to have associations with Mercury, the Roman god of communication and travel. Despite its delicate appearance, it is highly toxic to both humans and livestock, a trait that may have contributed to its mystical reputation. In the past, the presence of dog’s mercury was used to determine whether land had been continuously forested for centuries, making it a silent witness to Devon’s deep woodland history.

The unassuming yet ancient liverworts that cling to the damp stone walls and hedgerows of green lanes tell a different story. These primitive plants, some of the oldest life forms on Earth, have existed in one form or another for over 400 million years. Their presence is a quiet testament to the purity of the environment—these delicate organisms thrive only in clean, unpolluted air. In medieval times, liverworts were part of the Doctrine of Signatures, a belief system that held that a plant’s appearance indicated its medicinal use. Resembling a liver in texture and form, it was once used to treat liver ailments, though modern science has disproved its efficacy.

As the woodland edges stir with early birdsong, the song thrush (Turdus philomelos) begins to break the winter silence. Unlike its more boisterous cousin, the blackbird, the song thrush’s melody is intricate and repetitive, as if refining its song for the season ahead. In Victorian times, it was widely believed that thrushes could foretell the weather—if their song was particularly insistent, it was said to herald a coming storm. These birds also hold a place in British literature and poetry, notably inspiring the works of Thomas Hardy and Robert Browning, who admired the thrush’s defiant song as a symbol of hope and renewal.

Hidden within the cool waters of ponds and slow-moving streams, frogspawn makes its quiet appearance in early spring. This gelatinous mass of developing life has long been regarded as a symbol of fertility and transformation. In Celtic folklore, frogs were associated with the element of water and were believed to bring rain, making them an important figure in agricultural traditions. Their sudden appearance in spring also marked the moment when the land, long barren from winter, began to teem with life once more. Today, the presence of frogspawn is an important ecological indicator, revealing the health of local waterways and the resilience of amphibian populations.

On the first warm afternoons of the year, the buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) queen can be seen sluggishly emerging from her winter dormancy. Unlike the honeybee, which maintains a colony year-round, the bumblebee’s life cycle begins anew each spring, with a lone queen seeking out nectar and a suitable nest. Bees have been revered in folklore for centuries, often seen as messengers between the physical and spiritual worlds. In ancient Britain, it was customary to whisper secrets to bees, believing that they carried messages to the gods. The sight of a queen bumblebee searching for a nest is a small but vital moment in the renewal of life, as she will give rise to an entire colony of pollinators essential to the ecosystem.

On the woodland floor, the wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) shyly unfolds its white petals, often before the trees above have fully leafed out. This delicate flower is steeped in legend—according to ancient Greek mythology, it was created from the tears of Aphrodite as she mourned the death of Adonis. In the British countryside, it is sometimes called the “windflower” because it was believed to bloom only when stirred by the breath of the wind spirits. Traditionally, it was thought to bring luck if picked before noon, though, in reality, its brief bloom is best admired in situ, as it is a key nectar source for early pollinators.

Meanwhile, Devon’s verges and stream banks become dotted with the glossy yellow flowers of lesser celandine (Ficaria verna). The poet William Wordsworth, so captivated by its bright, star-like blooms, wrote three separate poems dedicated to the flower. In folk medicine, lesser celandine was once used to treat scurvy due to its high vitamin C content, and its roots, resembling small tubers, were believed to cure haemorrhoids—hence its old name, “pilewort.” Though dismissed by modern medicine, it remains one of the first flowers to bloom in spring, its golden petals reflecting the increasing daylight and the quiet return of warmth to the land.

These overlooked signs of spring may lack the grandeur of daffodils or the fanfare of cuckoos, but they each tell a rich, storied tale of nature’s awakening. They are remnants of ancient landscapes, bearers of folklore, and silent heralds of renewal. By pausing to notice them, we gain a deeper appreciation for the quiet, intricate symphony of spring’s arrival.

Singing Fields - Why Sound Matters in a Thriving Landscape

As the winter frost recedes and the first signs of spring emerge, the landscape at Mill Barton comes alive with the unmistakable chorus of birdsong. After months of quiet, the air is filled with the melodies of nature—proof that the land is stirring and that a new cycle of life is beginning. At Mill Barton, we take pride in the relationship between the land and the birds that call it home, the Red Devons that help maintain it, understanding that their song and presence is a direct reflection of the health of our environment.

The return of birdsong to our fields is one of the most joyous signs of the changing season. The first notes we hear are often those of the Snipe, its drumming call echoing over the damp meadows, a sure sign that spring is on the way. As the days grow longer, the Skylarks rise into the sky, their song pouring from high above the earth like a cascade of notes. The robins, tits, and blackbirds join in, each with their distinctive tune, creating a symphony that resonates throughout the hedgerows and fields.

Among these familiar voices, the delicate warbles of the Garden Warbler and Blackcap begin to emerge, filling the thickets and woodland edges with their fluid, melodious songs. The Chiffchaff’s repetitive, cheerful call is one of the most unmistakable sounds of early spring, a persistent reminder that the seasons are shifting. Soon, the Willow Warbler joins in, its descending, wistful notes carrying on the breeze, a sound that epitomises the gentle unfolding of spring.

But perhaps the most eagerly awaited call of all is that of the Cuckoo. Its distinctive, echoing song announces its return from Africa, a sound that has signified the arrival of spring for generations. The Cuckoo’s presence is fleeting, yet its call is deeply embedded in the rhythm of the countryside, a timeless marker of the season’s renewal.

Soaring Skylark on the farm, April 2024

Following swiftly are the Swifts and Swallows. These birds, who travel thousands of miles to return to our farm, bring with them the promise of warmer days and longer evenings. Their aerial displays and joyful chatter are a reminder of the incredible migration journeys they undertake and of the delicate balance of the natural world.

The chorus of birds that greets us each spring is not an accident; it’s a reflection of the careful stewardship we practise here on the farm. The birdsong we hear each day is directly tied to the way we manage the land. Unlike intensively farmed landscapes, where the focus is on maximising output at the expense of biodiversity, we’ve chosen a path that prioritises ecological balance.

One of the ways we do this is by maintaining species-rich hay meadows, which provide food and habitat for a wide range of wildlife, including birds. These meadows are not fertilised with artificial chemicals or treated with pesticides, meaning they remain full of the wildflowers and grasses that birds depend on. Skylarks and other ground-nesting species find shelter here, while insects and other small creatures thrive, ensuring a healthy food chain.

The hedgerows, too, are an essential part of the landscape. These corridors of nature act as vital refuges for nesting birds and insects, and they play a crucial role in supporting biodiversity. By allowing our hedgerows to grow freely and only cutting them when necessary, we ensure that they remain full of berries, seeds, and shelter for birds like Robins, Blackbirds, and Tits. The insects that buzz through the grasses and flutter through the hedgerows also provide an essential food source for the next generation of birds.

Our Red Devons, roaming across the meadows, play an equally important role in this delicate balance. These cattle are not just part of the landscape—they help shape it. Their grazing patterns create varied sward heights, which in turn allow different plant species to thrive, creating the perfect conditions for birds and insects alike. The careful management of our cattle ensures that the land remains healthy and diverse, providing a foundation for both wildlife and farming to coexist harmoniously. The Red Devons, with their calm temperament and low-impact grazing, work alongside the land and the birds to foster a thriving ecosystem.

Our farming practices may seem different from the typical agricultural model, but they are rooted in a deep understanding of how nature works. Birds, cattle, and the land work in harmony. The birds help control pests by feeding on insects, while also contributing to the health of the soil through their droppings, which fertilise the earth. The Red Devons, in turn, support biodiversity through their grazing, which helps maintain the open spaces and diverse plant life that the birds rely on.

By allowing the land to rest and recover, we encourage this natural collaboration. Fields left to grow long and wild support more wildlife, while our decision to avoid intensive farming allows the soil to retain its vitality and its ability to nurture life. This partnership between birds, livestock, plants, and soil forms the foundation of a healthy, sustainable farm, where nature’s cycles are allowed to unfold without interference.

As we start to see the first few flutters of spring, we’re reminded that a healthy landscape isn’t just seen—it’s heard. The return of birdsong signals that the land is thriving, that our efforts to preserve the balance between nature, birds, and livestock are paying off. Each bird call, from the first Robin of the year to the distant song of a Skylark, is a testament to the success of farming that prioritises biodiversity, patience, and care.

For us, the sounds of the farm are as much a part of the landscape as the fields themselves. As we listen to the chorus of birds that fills the air, we feel a deep connection to the land and to the creatures with whom we share it. And as the Swallows and Swifts return to, we know that our work is helping to create a space where nature can thrive— and where the sound of life will resound through the fields, echoing across the land for years to come.

From Meadow to Plate - The Power of Species-Rich Hay

At Mill Barton, our cows are more than just livestock—they are an integral part of our farm, our landscape, and our philosophy. We take immense pride in stewarding them with care, ensuring they live healthy, contented lives while contributing to a thriving, biodiverse environment. A key part of this approach is feeding them species-rich hay.

Species-rich hay is a diverse mix of grasses, legumes, wildflowers, and herbs that have grown naturally in meadows, rather than the monoculture ryegrass often found in conventional livestock feed. These meadows are brimming with plant life—red clover, yarrow, self-heal, bird’s-foot trefoil, and crested dog’s-tail grass, to name just a few. Unlike intensively farmed pastures, which focus on a single species of fast-growing grass, species-rich meadows create a balanced and nutritious diet for grazing animals. They also support essential pollinators, improve soil health, and help store carbon in the land.

A cow’s diet directly affects its well-being, which in turn impacts the nutritional quality of the meat it produces. Feeding cows a varied, natural diet has several key benefits. Cows evolved to eat a diverse range of plants, and a mixed diet supports their digestive system far better than a diet dominated by a single species of grass or processed feeds. Meat from cows fed on species-rich hay tends to have a healthier balance of omega-3 fatty acids and is richer in vitamins and antioxidants. When cows eat a balanced, natural diet, they stay healthier, reducing the need for supplements, antibiotics, or grain-based feeds.

Many scientific studies have compared the crucial ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids in grass-fed versus grain-fed beef. In all cases, the omega-3 to omega-6 ratio in grass-fed beef was found to be better than the recommended level of 4:1, while most grain-fed beef exceeded this level. Sixty per cent of the fatty acids found in grass are the omega-3 fatty acid Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA), which is formed in green leaves. When cattle are taken off grass and fed a grain-rich diet, they lose their valuable store of ALA and other beneficial fatty acids. In 2011, the British Journal of Nutrition published a study concluding that eating moderate amounts of grass-fed meat for just four weeks would give consumers healthier levels of these essential fats.

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), another type of fatty acid, has significant antioxidant properties and may be one of the most potent defences against heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. Beef is one of the best dietary sources of CLA, and 100% grass-fed beef contains significantly more of it than beef from grain-fed animals. Additionally, meat from fully grass-fed animals contains considerably more antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals such as beta-carotene and vitamin E than meat from grain-fed livestock.

The terms 'grass-fed' and 'pasture-fed' are often used interchangeably, but they are not the same. Under Defra rules, an animal only needs to have 51% of its diet based on grass to be labelled as grass-fed. In many cases, grass-fed systems still include significant amounts of concentrated feeds like barley and soya to speed up growth. In contrast, Pasture for Life producers ensure that animals eat only grass, herbs, and forage (including hay, silage, and lucerne) for their entire lives. This means no grain, no unnecessary concentrates—just a natural, species-rich diet.

There’s a well-known saying: you are what you eat. But it goes deeper than that—you are also what your food eats. When we eat meat from cows that have grazed on species-rich pastures, we are consuming the benefits of that diverse, natural diet. The nutrients, healthy fats, and minerals that the cows take in are passed along to us. In contrast, meat from intensively farmed animals raised on grain or processed feed often lacks the same nutritional profile. The same principle applies to environmental health. Cows that graze on species-rich hay help maintain meadow habitats, improve soil structure, and encourage biodiversity. This means that choosing ethically raised, pasture-fed meat isn’t just about taste and nutrition—it’s about supporting a healthier, more sustainable food system.

The impact of species-rich hay goes beyond the cows—it supports an entire ecosystem of wildlife. Traditional hay meadows are home to an incredible array of birds, insects, and small mammals. Skylarks, barn owls, and lapwings thrive in these open landscapes, while pollinators like bees and butterflies benefit from the diverse flora. By maintaining these biodiverse pastures, we also encourage the growth of native plant species, many of which are in decline due to intensive farming. Wildflowers such as devil’s-bit scabious, betony, ragged-robin, and meadowsweet not only add beauty to the fields but also play a crucial role in soil health and supporting insects that contribute to natural pest control. Restoring and protecting these meadows ensures that farming and nature can thrive together, rather than being in conflict.

Britain’s countryside was once rich with traditional hay meadows, but over 97% of them have been lost since the 1930s. By supporting farms that prioritise species-rich pastures, we help to reverse this trend, bringing back biodiversity and restoring soil health.

At Mill Barton, we see our cows as part of a bigger picture—one that connects ethical farming, landscape management, and great food. When you choose to eat meat from animals raised on species-rich hay, you are making a conscious decision to support better farming, healthier animals, and a more balanced countryside.

Where Rivers Run Wild Again: The Art of River Restoration

Introduction to River Restoration

River restoration is a process that seeks to return rivers and streams to a more natural and functional state, addressing the damage caused by centuries of human activity. Many rivers in the UK have been straightened, polluted, or obstructed, leading to issues such as increased flooding, reduced water quality, and a loss of biodiversity. In response, a variety of restoration strategies are employed to improve these vital ecosystems.

These strategies include removing artificial barriers, reintroducing natural meanders, and enhancing habitats for wildlife. While it’s often not possible to fully restore rivers to their original condition due to irreversible changes in the landscape and human dependence on water resources, rivers are resilient and capable of recovery when given the right support. Restoration efforts focus on aiding this recovery by addressing hydrological, morphological, biological, chemical, and societal challenges within the catchment area.

The aim is not only to improve ecological health but also to create more resilient landscapes and cleaner water systems. Restoring features such as migration routes for fish such as salmon or reintroducing native vegetation along riverbanks which enhances biodiversity and helps to restore natural river processes. River restoration goes beyond ecology—it is about preserving the beauty, function, and sustainability of our waterways, ensuring they can thrive for future generations.

Re-meandering and Brash Dams: Reviving Natural River Dynamics

One of the most effective techniques in river restoration is re-meandering, which involves reintroducing the natural curves and bends that rivers often lose due to human intervention. Straightened rivers may seem more efficient, but they disrupt the flow dynamics, increase erosion, and reduce habitats for aquatic and riparian species. By restoring these meanders, rivers slow down, allowing sediment to settle naturally, reducing flood risks downstream, and creating varied habitats for fish, insects, and plants.

Natural Flood Management (NFM)

NFM is an innovative approach that uses the power of nature to reduce the risk of flooding and improve the resilience of landscapes. Also referred to as Natural Water Retention Measures (NWRM) or Nature-based Catchment Management (NbCM), NFM focuses on restoring or mimicking the natural processes that once governed rivers, floodplains, and the surrounding environment. By allowing rivers to function more like they did before human interventions, NFM helps slow the flow of water, which can significantly reduce flood risk downstream. But it does more than that—by enhancing the ability of the landscape to retain water, it also helps to make land more resilient to drought conditions by releasing water more slowly over time.

NFM involves a variety of techniques designed to work with nature, rather than against it. For example, leaky dams—constructed from wood, stone, or other natural materials—are placed in streams to slow water down and allow it to spread out, reducing the speed and volume of water downstream. Swales, which are shallow, vegetated ditches, can be used to capture rainwater and direct it away from vulnerable areas, while offline ponds hold water temporarily during heavy rainfall, preventing it from overwhelming the river. Remeandering rivers helps restore natural curves, allowing water to slow down and spread out rather than rushing in a straight line. In addition, land management practices such as controlled grazing, reforesting, and planting cover crops improve soil health, making it more absorbent and reducing surface runoff. Soil management also plays a key role by improving infiltration and reducing erosion. Finally, the reintroduction of beavers can play a vital part in flood management, as their dam-building activities naturally slow water and create wetland habitats, which help retain water and reduce flood peaks.

Alongside re-meandering, smaller interventions like brash dams play a crucial role. These simple structures, made from natural materials like branches and twigs, are placed across the river or its tributaries. Brash dams mimic natural woody debris, slowing water flow, trapping sediment, and creating pools and riffles. These features are vital for aquatic life, offering spawning grounds for fish and habitats for invertebrates.

Stourhead Estate and Panford Beck

In our recent projects at Stourhead Estate in Wiltshire and along Panford Beck in Norfolk, we've successfully implemented some of these techniques to restore natural river dynamics.

Stourhead Estate Masterplan

At Stourhead Estate, renowned for its 18th-century landscape gardens, the original design included the creation of a large artificial lake by damming the River Stour. Over time, sediment accumulation and changes in water flow necessitated restoration efforts to maintain the lake's health and aesthetic appeal. By reintroducing techniques as above, we've helped to enhance water quality, reduced sediment build-up, and revitalised habitats for local wildlife.

Similarly, at Panford Beck, a tributary of the River Wensum in Norfolk, we've applied these restoration techniques to great effect. These interventions have also contributed to better flood management, helping the return of native species and increased resilience of the local ecosystem.

These projects demonstrate how combining traditional landscape aesthetics with modern ecological restoration techniques can yield benefits for both heritage sites and natural environments.

What is Stage 0 Restoration?

Stage 0 restoration is a cutting-edge approach to river restoration that aims to reset a waterway to its most natural, undisturbed state. Unlike traditional restoration methods, which often involve specific interventions such as remeandering or installing brash dams, Stage 0 focuses on reconnecting a river with its original floodplain and allowing it to flow freely across the landscape. This process often involves removing artificial barriers, drainage ditches, and embankments, essentially giving the river permission to behave as it would have before human interference.

A prime example of Stage 0 restoration in the UK is the National Trust’s Holnicote Estate project on Exmoor. This groundbreaking initiative has transformed the waterways of the estate by completely rewilding sections of the river. Instead of following a straightened course or even a carefully engineered meander, the rivers at Holnicote are now allowed to spread, braid, and create their own paths across the floodplain.

The results have been remarkable. Flood risks downstream have decreased as water is naturally slowed and absorbed across the landscape. Sediments are deposited where they would have been historically, improving soil health and reducing silting in downstream rivers. Wildlife has flourished too, with wetland habitats returning to support species like otters, water voles, and wading birds. The benefits aren’t just ecological; local communities benefit from improved water quality, reduced flooding, and a restored landscape that’s more resilient to climate change.

Stream evolution model (Cluer and Thorne 2013). Stage descriptions are provided in Table 5. Dashed arrows indicate "short circuits" in the normal progression.

A Ripple Effect

Whether it’s through re-meandering, brash dams, or Stage 0 restoration, river restoration projects across the UK are proving that working with nature, rather than against it, can deliver lasting benefits for both wildlife and people. Projects like those at Stourhead Estate, Panford Beck, and Holnicote Estate demonstrate the power of these techniques to transform our waterways and landscapes.

By restoring rivers to their natural state, we’re not only repairing the damage of the past but also creating resilient ecosystems that can thrive for generations to come.

Threads of the Wild: Hedgerows and the Fabric of Nature

Farming and wildlife are deeply interconnected, often in subtle yet profound ways. While modern agricultural practices have focused on maximising yields, these changes have often harmed wild plants and animals. Rare species have become rarer—or even extinct—and even once-common species have disappeared from vast areas of the UK. This loss doesn’t just impact nature; it ultimately threatens farming itself.

Without healthy ecosystems, the land’s productivity diminishes, and farming becomes less sustainable. Wild species, from pollinators to soil-dwelling organisms, play vital roles in maintaining a balanced and fertile landscape. Among the many opportunities to restore this balance, hedgerows stand out as a simple yet impactful starting point.

Hedgerows: A Bridge Between Farming and Nature

Hedgerows are much more than field boundaries. When allowed to grow bushy and overgrown, they create incredible habitats for birds, insects, and other wildlife. Yet hedgerows have often been casualties of modern farming practices, including removal for larger fields or intensive cutting.

Restoring and managing hedgerows with wildlife in mind offers a practical way to make space for nature while supporting the farm itself. A thriving hedgerow not only provides shelter and food for species like yellowhammers, robins, and fieldfares but also supports pollinators, improves soil health, and offers natural pest control.

The Role of Native Species

Native plants are vital for creating hedgerows that truly benefit biodiversity. They provide food and shelter to the species that have evolved alongside them. Here are some key native plants and the wildlife they support:

Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna): Produces berries (haws) that feed birds like blackbirds and redwings. Its dense branches also provide excellent nesting sites.

Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa): Its early spring blossoms are crucial for pollinators, and its sloes feed birds like thrushes.

Hazel (Corylus avellana): Supports a variety of insects, and its nuts are a key food source for mammals like dormice and birds like jays.

Dog Rose (Rosa canina): Provides rose hips that are rich in nutrients for birds and mammals during winter.

Birds That Benefit from Hedgerows

Bushy, overgrown hedgerows create a haven for many bird species, including:

Yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella): These bright yellow birds nest at the base of hedgerows and feed on seeds and insects.

Robin (Erithacus rubecula): A familiar sight, robins use hedgerows for nesting and foraging.

Bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula): Hedgerows provide the seeds and berries that bullfinches rely on.

Fieldfare (Turdus pilaris) : In winter, these migratory birds feed on the berries of hawthorn and blackthorn.

Whitethroat (Sylvia communis): This summer visitor thrives in the dense vegetation of unmanaged hedgerows.

Number of bird species and average number of pairs per 100m in different hedge types - Kenneth Mellanby: Farming and Wildlife (1974)

The Impact of Modern Farming Practices

As we consider how to manage hedgerows, it’s important to understand their role in the broader farming landscape.

Hedgerow Removal: The removal of hedgerows to create larger fields has fragmented habitats and reduced biodiversity.

Pesticides and Soil Health: Chemical use and changes in soil management have reduced populations of beneficial soil organisms—overlooked but vital forms of wildlife.

Land Drainage: While beneficial for arable farming, drainage can harm wetlands, further depleting wildlife habitats.

Grassland and Cropping Changes: Shifts in grassland and arable cropping practices have also reduced habitats for insects and ground-nesting birds.

Each of these changes highlights the delicate balance between farming and nature. Hedgerows, when managed thoughtfully, can act as a counterbalance, supporting wildlife even amid intensive farming systems.

Hedge Type Produced by Different Management - Kenneth Mellanby: Farming and Wildlife (1974)

How to Restore Hedgerows for Wildlife

Encourage Overgrowth: Let hedgerows grow bushy and dense, providing multiple layers of habitat for birds, insects, and mammals.

Reduce Cutting: Trim hedgerows on a rotational basis every two to three years, allowing plants to flower and fruit to support biodiversity.

Include Native Plants: Incorporate species like hawthorn, blackthorn, hazel, and dog rose for their ecological benefits.

Protect During Nesting Season: Avoid trimming from March to August to safeguard nesting birds.

Integrate Hedgerow Planning: Systematic management of hedgerows ensures they remain both stockproof and ecologically valuable.

Wildlife Benefits Farmers Too

The presence of wildlife isn’t just a bonus—it’s essential. Birds, insects, and soil organisms help control pests, pollinate crops, and improve soil health. A well-managed hedgerow becomes a refuge for these species, contributing to the farm’s overall productivity and resilience.

A New Perspective on Farming and Nature

Making space for nature on a farm starts with small, thoughtful changes. Hedgerows, which bridge the gap between farmland and wild spaces, are a perfect first step. By managing hedgerows with biodiversity in mind, farmers can create habitats that benefit both wildlife and agriculture.

In the end, a farm that welcomes nature becomes more than just a space of production—it transforms into a thriving, balanced ecosystem that benefits wildlife, the environment, and the farmer alike.

Lannock Farm: Rooted in Sustainability, Growing with Innovation

Lannock Farm courtyard in progress, November 2024

Situated in the village of Weston, North Hertfordshire, Lannock Farm is a place where people can connect with nature, driven by a strong commitment to sustainability and fostering a thriving environment. Nestled amidst the serene rural landscape of Hertfordshire, the farm is surrounded by expansive arable fields and scattered pockets of pasture.

With five generations of family care, the farm has developed a deep-rooted connection to the land and the local Weston parish. This bond is complemented by an innovative and forward-looking approach to farming that emphasizes regenerative practices. These practices aim to improve soil health, enhance biodiversity, maintain water quality, and provide opportunities for people to flourish in a countryside setting.

Lannock Farm also offers a distinctive workspace tailored for businesses in the food and beverage, farming, and creative industries. These spaces are ideal for enterprises seeking to innovate, collaborate, and drive positive change within their fields. By being part of this supportive and progressive community, businesses can thrive while contributing to a sustainable future in the heart of the countryside.

Lannock Farm : In The Words Of Alex Cherry

Digg&Co has been working with us on the Grainworks project at Lannock Farm for over five years, and their contribution has been integral to bringing our vision to life. From the very start, their early conceptual ideas were not only imaginative but also deeply attuned to the specific character of the site. They helped us understand the profound connection between the land itself and the surrounding farmland, which was crucial to the overall design process.

The design team took the time to listen to our ambitions, as well as our concerns, and managed to translate these into a design that was both functional and inspiring. Their ability to take abstract ideas and turn them into something tangible was remarkable. What stood out, in particular, was Toby’s skillful use of pencil on stencil paper. His delicate yet precise drawings were a reflection of his vast knowledge and experience in landscape design, enabling us to visualize the project more clearly and discuss it in a way that felt natural and collaborative.

As we move from plans to action — laying paving slabs and seeing the first hints of the design take shape — the joy of the project becomes more apparent every day. The people who live and work on the site are starting to see the tangible benefits of all the hard work, and the space is beginning to come alive in a way that’s truly rewarding.

Landscaping is often the aspect of a project that gets pushed to the bottom of the to-do list, particularly on a project like this. However, at Lannock Farm, we’ve come to realize just how vital the outdoor spaces are in making the site truly unique. The landscaping not only enhances the aesthetic value of the place but also plays a significant role in fostering a sense of community. A well-designed outdoor environment can make a huge difference in creating a happy and thriving space where people can work, collaborate, and feel inspired.

Throughout the entire journey, Digg&Co. has been there for us, offering invaluable guidance and support. They are currently assisting us with a planting plan that will further bring the space to life and create a vibrant, sustainable environment for years to come. We’re excited to see the outcome and couldn’t be more pleased with the collaboration so far.

Harold’s Park (Nattergal)

Harold’s Park Wildland Masterplan and Illustration by Quentin Martin (2024)

Harold's Park Wildland, located in the Epping Forest District, serves as a key environmental project aimed at reconnecting millions of city dwellers with nature. The project, led by Nattergal, seeks to enhance biodiversity and encourage people to engage with the natural environment in their urban surroundings.

Nattergal's role as custodian offers a unique opportunity to foster environmental improvements such as water purification, habitat restoration, better soil health, and flood risk reduction. In addition to these ecological benefits, the project aims to create local employment opportunities and provide educational experiences for children in both London and Essex, allowing them to explore and immerse themselves in nature.

Although Harold's Park might initially appear lacking in biodiversity, Nattergal have uncovered valuable habitats, including ancient woodlands, veteran oaks, species-rich grasslands, ponds, scrubland and scrapes. These untamed treasures provide Nattergal with the perfect foundation to begin nature’s healing process, sparking a transformation that promises to bring both wildlife and people together in harmony.

One of the most exciting prospects for Harold’s Park is the restoration of its waterways, which could play a pivotal role in reviving rare species lost to decades of intensive farming. These rejuvenated streams and ponds will become lifelines for wildlife, creating rich habitats that beckon back creatures long absent from the land.

Harold’s Park is steeped in history, its roots stretching back to the days when it served as a deer hunting ground for King Harold II. Over the centuries, the land transformed, becoming an agricultural hub before evolving into the dynamic landscape it is today. In the 1950s, Scottish farmer John Mackie acquired the farm with a vision that went beyond traditional food production. He saw Harold’s Park as a place where farming could coexist with nature, planting trees and inviting the public to experience the countryside's beauty.

In the 1970s, Mackie’s son George took over the farm's tenancy and expanded its horizons. Under his stewardship, the farm diversified beyond its arable roots. George established an equestrian business, added the charm of Christmas tree farming, and opened the park’s ponds, enriching the landscape with both leisure and purpose.

In 2024, Nattergal stepped in with a bold vision, purchasing the site to rewild and restore its natural beauty. Now, under Nattergal’s custodianship, Harold’s Park embarks on an exciting new chapter. The land will be nurtured back to its wild roots, allowing wildlife to return.

Harold’s Park lies just a stone’s throw from London, offering a unique opportunity for city dwellers to escape into the wild without having to travel far. Its proximity to the capital makes it a convenient destination for millions, providing an accessible gateway to the wonders of the natural world.

For those living in London and Essex, the rewilding of Harold’s Park opens up a chance to reconnect with nature in a way that few urban cities can offer. Within an easy reach of the city, families, schools, and individuals can explore landscapes teeming with wildlife.

The restored wetlands will attract cranes—majestic birds that had vanished from the region. The Brown Hairstreak Butterfly will also play a crucial role in the rewilding of Harold’s Park, symbolising both the fragility and resilience of the ecosystem. This rare and beautiful butterfly, once widespread, has suffered due to habitat loss, particularly the destruction of hedgerows and woodland edges. As the butterfly flutters through the restored meadows and woodland edges, it will help pollinate wildflowers, contributing to the regeneration of native plant species, including Yellow Flag Iris and white waterlilies near the park’s wetlands. Its delicate wings will be a sign that Harold’s Park is once again becoming a thriving, interconnected ecosystem—a place where even the smallest species play a vital role in maintaining the balance of nature. Among the butterflies, the restoration will also see the return of the striking Marbled White Butterfly, which will flutter through the park’s sunlit meadows, contributing to the pollination of species like Broad-leaved Helleborine, an elegant orchid that will once again grace Harold’s Park.

A few examples of the species that will inhabit Harold’s Park Wildland

Beyond the water’s edge, the woodlands will become a refuge for red kites, which will soar above the ancient forest. Long-eared owls will make their home in the restored hornbeam coppice and veteran oaks, their timeless canopies providing shelter and sustenance for a rich variety of birdlife and mammals. The return of the Red-backed Shrike and Goshawk will bring back the thrill of natural predation. Known for its sharp hunting skills, the Red-backed Shrike (often referred to as the "butcher bird" for its habit of impaling prey on thorns) will make its home in the park’s hedgerows and scrubland, where it can hunt insects, small mammals, and birds.

On the ground, Nattergal plans to bring back New Forest ponies and White Park cattle, large herbivores that will naturally manage the landscape through grazing, helping to maintain a balanced ecosystem. These animals will encourage the growth of wildflowers and support the return of pollinators like bees. As the park’s meadows and hedgerows come alive, they’ll also support smaller species such as grass snakes and Harvest mice. Hornbeam coppice and majestic veteran oaks will continue to stand tall, becoming the backbone of Harold’s Park’s restored natural beauty and providing shelter to the Goshawk and Lesser-spotted woodpecker.

This rewilding project will not only restore the wildlife that once graced Harold’s Park but will also offer a sanctuary for people, giving them a space to reconnect with the land and witness the rebirth of a vital ecosystem—one where New Forest ponies, red kites, cranes, and even the delicate Brown Hairstreak Butterfly can coexist in perfect harmony.

A Guardian article on Harold’s Park Wildland written by Patrick Barkham (2024)

Creating and Maintaining Scrapes for Waders - Harry and Toby Go Digging

Harry, Bella and Toby recently began managing a silage pasture on the edge of a well-established, marsh-fritillary rich tussocky culm grassland, but the fields were anything but easy to work with. The land is constantly wet, owing to its flat topography and clayey subsoil. Water holds on this land naturally, and it was clear that rather than continuing with regular silage cropping, it would be much easier to shift gears and embrace our natural farming methods.

The goal was simple: let the land flourish naturally, with a little bit of initial mechanical intervention, and in doing so, encourage biodiversity, improve water retention, and protect the carbon rich soil.

One piece of this new direction was the creation of scrapes—shallow depressions designed to hold water. These scrapes would serve multiple purposes: providing natural watering points for grazing cattle, helping restore the land to a more species-rich grassland and attracting a variety of wildlife, particularly wading birds and insects. The hope was to welcome back species like snipe, woodcock, golden plover, and, in time, lapwings and curlews.

The first step was to assess the land. The existing rye-dominant grass sward was cut back, yielding a strong crop of hay. This allowed them to get a clearer picture of the land's natural contours. Though the fields seemed flat at first glance, subtle dips and ridges soon became apparent—ideal spots to create pockets of standing water. With a five-ton digger (Toby) and a six-ton dumper (Harry) on hand, they set to work. There was no pre-determined plan, just an open-minded approach of digging and shaping the land as it suggested. The process was relaxed but purposeful, with lots of back-and-forth discussion about the depths, curves, and edges of each scrape.

In just two days, the first phase was complete. The scrapes, with their varying depths and gradients, provided a range of wetland habitats that would attract different species. Six months later, the results were already visible. The site is becoming a haven for wildlife: snipe had appeared, and red deer had started to frequent the area. Dragonflies, swallows, and house martins were also drawn to the new water features, and the site was alive with the sounds of meadow pipits and woodcock. The wet areas around the scrapes had begun to expand, and the vegetation was slowly filling in. As the years go on, they expect the species count to continue growing.

The success of this project shows how simple conservation measures—like creating ponds and scrapes—can have an immediate, transformative effect on the environment. The transition from a silage field to a wet culm grassland has brought about a noticeable increase in ecological activity, and the results have been incredibly rewarding. The takeaway? Sometimes, the best way to make a real difference is to get out there, grab a digger, and start creating scrapes. The land knows what it needs, and with a little help, it can quickly start to thrive.

Haymasters 2024 - While the sun shines

On the weekend of the 13th-14th of July we all came together at Mill Barton for a delightful haymaking event that celebrated the timeless tradition of harvesting hay. Haymasters was a vibrant mix of hard work, camaraderie, and fun, bringing together people of all ages to participate in this essential agricultural practice. Here's a recap of the memorable weekend filled with sunshine, laughter, and plenty of hay.

The first task was cutting the grass, for which scythes were provided. Under our experts' guidance, everyone got to try their hand at swinging the scythe, an art that requires both strength and finesse. It was a sight to behold – rows of enthusiastic participants, scythes in hand, cutting the tall grasses under the clear blue sky. There's a certain rhythm to the process – cutting the grass, spreading it out to dry, and turning it to ensure even drying. It's labor-intensive, but there's something incredibly satisfying about seeing the progress we've made by the end of the day.

Rob Wyld in the wild surveying the hay

As the evening approached, we left the hay to dry and gathered around the firepit. After a day of hard work, there's nothing quite like sitting around a fire with friends, plenty of cider, and a grill loaded with burgers. The conversations flowed as freely as the cider, and the burgers were grilled to perfection.

A beautiful summers evening barbecue

Sunday was dedicated to rickmaking. The hay had dried sufficiently by now, and it was time to build the ricks. This task requires teamwork and precision. We worked together, stacking the hay neatly and securely.

Process of rick-making

In the afternoon, there were demonstrations of various traditional haymaking techniques, including the art of haystacks. We also learned about the importance of timing in haymaking – cutting the grass at the right stage of growth and ensuring it dries properly to retain its nutritional value.

The triumphant feeling of creating a perfect rick

As the sun began to set, we gathered for a feast. The centrepiece was a delicious brisket made from Mill Barton beef. Slow-cooked to perfection, it was tender and flavorful, a true testament to the quality of our meat. Sharing this meal was a fitting end to a weekend of hard work and celebration.

Sophie observing the rick-making

Haymasters was a resounding success, thanks to the enthusiasm and participation of everyone involved. It was more than just an agricultural activity; it was a celebration of our heritage and community. As we head into the rest of the summer, the memories of this weekend will linger, reminding us of the joys of working together and the importance of preserving our traditions.